It rains here.

Yes. Well, because it’s the Amazon rainforest, duh.

No. I mean, it really rains.

One minute you are walking down the road or swimming in the river with the equatorial sun beating down on your head. Next, you are diving for cover.

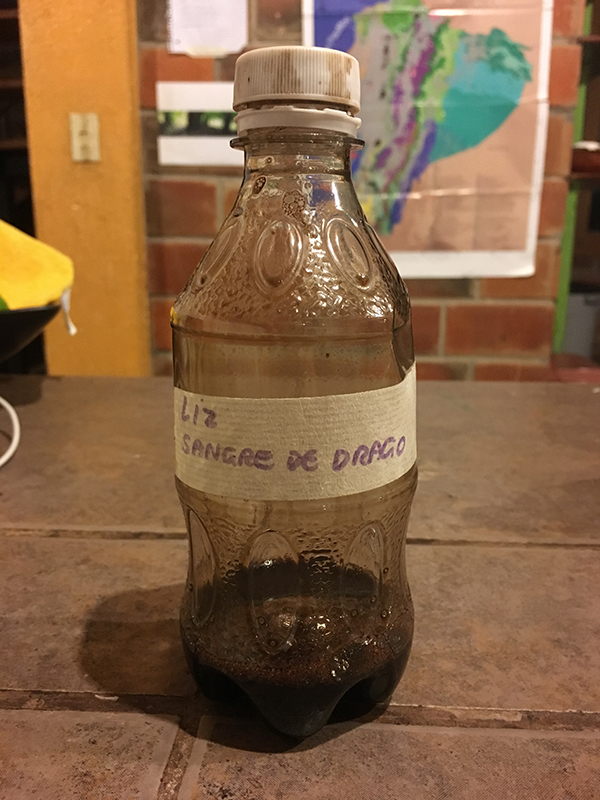

Last week, I took a weekend trip to Puyo, two hours away, to visit a beautiful ethnobotanical park called Las Yapas, where a devastated block of farming land has been lovingly transformed into an oasis of endangered Amazonian orchids and traditional plant medicines (dragon’s blood, anyone?). The park owner’s mother, Yolanda, was in the middle of giving me an individualised tour. We stood in the middle of the forest while she explained about biochar and pioneer species; next second: “Run!” (or as you can imagine, in Spanish: “¡Corre, corre, corre!”). When we got back to the house I stood stripped down to underpants and a borrowed towel while my clothes took a lengthy spin around the dryer. I don’t think I’ve ever been so wet in my life. Oh, except for that one time I went ocean kayaking in a thunderstorm in Costa Rica.

Medicinal plants at Las Yapas; go and visit on a weekend, especially if you are into agroforestry and ethnobotany, which are two major reasons why interns come here to the Amazon.

Just to prove my point, the Rio Misahuallí (which runs right past the house wherewe interns hang out) is pretty amazing. It carries a ton of water out of the Andes into the Amazon watershed, the world’s most biodiverse region. But it does not usually look like this …

Flooding Misahualli

Enough about rain. Let’s talk about Amazon Learning and my internship project with Fundación Runa.

No, let’s keep talking about rain. It’s such a part of life here.

My internship is in the area of community development. Myself and three other interns are currently travelling to Kichwa communities and talking to leaders and producers in thirteen guayusa cooperatives. We’re collecting data that hopefully will help Fundación Runa understand the different roles of men and women in the guayusa value chain. Usually we do our interviews after community meetings, or asembleas, where Runa meets up with the local farmer’s association to monitor how their production and sales are going, or develop new products that will help farmers diversify and receive more returns through the fair trade system.

One of the dry days in the office

Several of our interviews have been conducted through the background noise of an afternoon thunderstorm. My Spanish isn’t wonderful on a good day; imagine trying to pronounce ‘capacitaciones’ while being deafened. The other day we were all literally held hostage in a porch at the back of a house talking with a family of guayusa producers, while the yard flooded around us. It was a good opportunity for the family to have a mini-market: they showed us their delicious lettuces (which became the house salad that night) and laid out their fine beadwork for us. Time is never wasted here.

One time the rain waited until we were piled in the back of a truck getting a lift out of a rural community down to the main road. While I sat squashed in with half the community and a cooking pot and a large bag of potatoes and a foam mattress, we proceeded slowly down the dirt road. Ten minutes later we let the women and mattress and potatoes and cooking pot off at the bus stop, leaving me and a farmer still in the back. A few seconds after that, down it came. From then on we both sat huddled together under my skimpy raincoat, having a disjointed conversation that between Kichwa, Spanish and English translated to: “Oh my god, we are getting so wet.” Cross-cultural relationship building at its finest.

The point of this blog is not just to talk about the project and about Runa, but do to it in a way that captures the feel and the essence of being here in this rich, green, steaming, culturally and ecologically diverse place. Because if you are thinking of coming here, it’s not just to do your master’s degree placement. It’s not just to be part of an NGO that is a world pioneer in fair trade guayusa tea production and community empowerment. It’s to experience the back woods of Ecuador, a country that is not well-marked on the traveller’s map compared with its bigger and more famous neighbours.

Ecuador

I am from Australia, and a common response when I first announced to people I was coming to Ecuador (the first time; I’ve now made three visits) was: “Oh … um … okay … is that in … Africa? No! Wait! It’s somewhere in South America, isn’t it?” Yeah, I reply. That’s kind of why I’m learning Spanish. “Oh, is that what they speak there?”

So I consider it my duty to educate people back home, not only about the existence of Ecuador, but what it’s actually like to be here. The way the Andes carve up the country into sections that contrast so powerfully to each other that when you’re in one part, you can’t imagine being anywhere else. You’re on a baking hot deserted beach with a humpback whale surfacing right next to you. Or you’re sight-seeing the world heritage colonial centre of Quito and running out of breath halfway up the hill because it’s 2800 metres above sea level, and the air’s so clear and brilliant and dry the buildings look as if they’ve been airbrushed. Or - in my favourite bit – the Amazon – you can forget the rest of the world even exists.

I need to be clear at this point: We’re not in the jungle jungle. We’re not floating down a river in a dugout with monkeys leaping overhead. That is absolutely amazing, and you can do any number of tours here that take you out into the real thing. This area, the upper Napo region, has been farmed for centuries. But it is still the Amazon. It’s still green and lush and full of butterflies and birds (and yes … every possible kind of bug). It is the headwaters, where all the rain collected on the mountain slopes – all the rain I’ve just been talking about – flushes down rivers that join bigger rivers that join even BIGGER rivers that eventually join the Rio Amazonas, which takes it all the way to the Atlantic coast. By virtue of this connectivity, everything that happens here – the rain, the sun, human activity – is important. Everything we do here impacts on the millions of hectares of fragile ecosystems stretching across Peru and Brazil. This region is the source of life.

Think about things this way, and it changes your whole perspective on your project here, be that agroforestry or community development or social enterprise building. Consider the mission of Fundación Runa: when we help empower Kichwa farmers to make income from their traditional, sustainable farming methods we’re giving them a livelihood option that doesn’t involve monoculture, imported crops, pesticides. It enables people to stay in their communities and keep a strong connection to their culture. In turn, they can teach us a lot about how to respect Mother Earth.

And it’s not just while at work that you are helping the Amazon. When you’re swimming, learning about traditional medicines (I have mastered the art of uña de gato tea), building relationships with your host family, doing tours, rafting, reading about the history and cultures of this place, you’re filling yourself up with experiences and learnings that you take back home to educate others and inspire them to love and protect the forest, too. You become messengers of hope. You become change agents.

Or not. (Here quoting my mum after I did a facebook rave about a particularly large tarantula we found in the house: “Just saying this again, Liz, I am so-o-o not coming and visiting any time soon!”).

So to capitulate: there’s one final thing I want to say. If you come here … enjoy the rain. Revel in it! Love it. Know how vital it is – giving life to the soil, the worms, the guayusa, the rivers, the forest, the cacao seeds that produce your to-die-for dark artesanal chocolate. Even when it comes through the roof and through your mosquito net and onto your top bunk bed and you end up with a wet head, breathe deep and apply the art of zen. Consider it an initiation into the elements of nature. You are being annointed by the spirit of the rainforest. And your life will be so much better for it.

Liz Downes

Summer 2017